Apologies for the gap in service; I had high hopes for a weekly email, but I variously got sick, lost in Wales, and distracted. Let’s just agree that these emails will be semi-regular for the time being..

Yes, it rained.

I was in Manchester this week recently, at the annual conference of the European Network for Short Fiction Research. I listened to presentations of papers on the various complexities of short fiction - on representations of dementia, on cancer narratives, on the traditions of the Irish literary journal, on the post-humans of BrexLit, amongst others - all of which were fascinating and thought-provoking and scrupulously-researched.

And then, lol, it was my turn.

Where does neoplatonism fit into all this?

You’ll be familiar, I’m sure, with that particular nightmare in which you suddenly find yourself pushed on to a stage holding, variously, a guitar or microphone or Yorick’s skull, without knowing your lines or the chords or why you’re not wearing any trousers. My version of this nightmare is to be in the Radio 4 studios for a recording of Start the Week, only for Melvyn Bragg to turn to me and ask, in his trademark wry drawl: “So, Jon, where does neoplatonism fit into all this?”

And in real life, almost every time someone asks me a question at a literary festival, or in an interview, or at a conference, I can mostly just hear something about neoplatonism. It was baffling to me, when I first did literary events, how many opinions I was expected to have, and how many of those conversations were framed as literary criticism. I’m still baffled by the detail with which I’m sometimes expected to articulate my own writing practice. But I really don’t know what I’m doing, I always want to reply. I wondered, flippantly, if I might base a keynote presentation around that theme. And the more I thought about it, and about my own writing and teaching – and the more I realised that I don’t even know what a ‘keynote’ is – the more this made sense. So I stood in front of a room of experienced colleagues, writers, and academics, and explained why having no idea what I was doing was a good thing, actually.

Here’s some of what I said:

Writers are not experts

Each time I write a story, or a novel - or a keynote presentation - part of the challenge and interest comes from working out what I’m trying to do, and how to do it. If I wanted to write my last novel again, I might know how to do that. If I wanted to teach my students how to write my last novel, I could have a crack at that. But I don’t want to write my last novel again. And I don’t want my students to write my novels; I want them to write theirs.

Language is a shared system of meaning, but the sharing is an imperfect and unstable process. Every time we try to communicate, we’re looking for the right words. Every time we try to tell a story, we’re working it out all over again. Writing is difficult, is what I’m saying, and most of the time we don’t know what we’re doing.

The best creative writing teaching acknowledges this uncertainty; the less-valuable creative writing teaching, I’ve come to believe, glosses over the uncertainty entirely by banging on, mannishly, about craft. There are rules we can give you about writing, these teachers announce. There are disciplines in which you can train. These rules are all over the internet, and I’m not going to link to them, but they say things like: remove all the adjectives, strip out the baggy sentences (or the florid phrases, or, who knows, the effeminate words?), show don’t tell, cut to the action, kill all the first-born children and burn all the crops in all the fields.

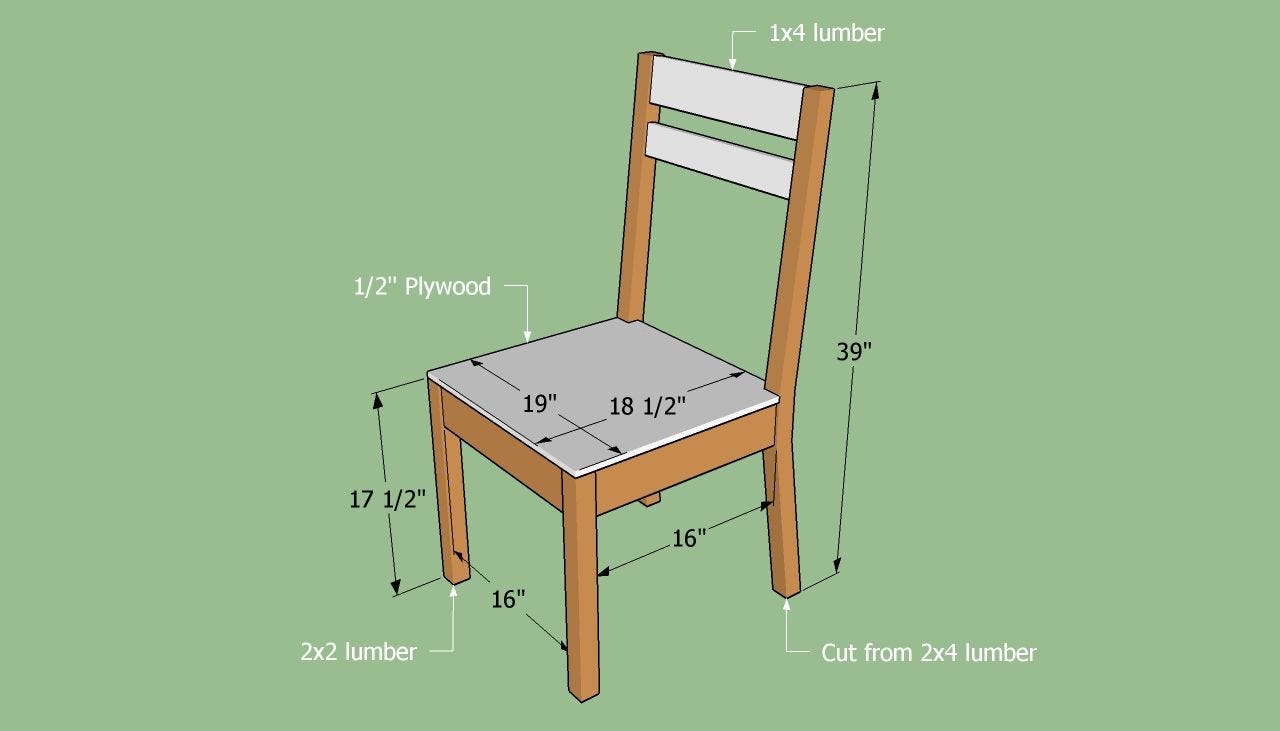

And I think it’s interesting that when people talk about the ‘craft’ of writing, they’re generally not talking about crafts like knitting, or weaving, or quilt-making, even though those would be pretty good metaphors for writing. No, they’re talking about crafts that involve big sharp tools, overalls, workshops with noisy extraction fans. Something like chair-making.

But a story is not a chair, and a chair-maker is not a writer. A chair-maker gets good at making chairs by making lots of chairs. A chair-maker knows that a chair needs to be strong and robust; it needs a back, a seat, four legs, a certain sense of chairness. A chair is for sitting on without breaking. But what is a story for?

When we start writing a story, we don’t know what it will be for, or what it will do, or how it will do it. We don’t know how we will make it. We can draw on our previous experience of writing stories, and especially on our previous experience of reading stories (and analysing those stories, and thinking about those stories, and talking with our fellow readers and writers about those stories, and this little bit here in parentheses is essentially my vision of what a writing class could be), but when it comes to this story that we’ve right now started working on, we don’t, if we’re honest, have any idea what we’re doing.

If I’m completely honest, I think I’ve too often skirted around this in my own teaching. I’ve worried that the students arrive at my classes expecting expertise, and that it’s part of my job to reassure them by looking as though I possess it. What I would really like to say, at the start of a semester, is something like this:

I do have some experience of writing, and rewriting, and talking to other writers about their work. I have learnt some things along the way. But I’m not an expert. And I’m especially not an expert in the story that you’re trying to write. Shall we talk about it?

My favourite phrases in the classroom are the ones that the students tend to be least fond of:

Maybe.

I don’t know.

What do you think?

Next time: a few examples of the kind of thing I mean by ‘teaching without expertise’ (and, by extension, writing without expertise; writing with uncertainty, writing with doubt, writing with an openness to this time being completely different from the last time).

Class dismissed.