Are you ready?

Some of you are new here today, and some of you have been with us for some time. All of you are welcome. A quick reminder that these notes come out of the teaching I do at the University of Nottingham, but are open to everyone. And that since I’m not actually teaching this term these notes are particularly freeform and speculative.

What are we doing here?

One of the problems with talking or thinking or writing about writing, and certainly with actually getting started on doing some writing, is that the baggage of ideas about Writers and Writing can be kind of heavy. Cumbersome. Distracting. We’ve been told what writers look like, and they don’t always look like us.* We’ve been told what Good Writing looks like, and it doesn’t always look like the writing we do. Perhaps we’ve moved past the image of the writer in his garret – perhaps we’re no longer sure what a garret really is? – but I think the idea that writing must be done alone, in silence, and in some special space, by some special person, still exists. The popular notion of the ‘writing retreat’ attests to this – retreating from what? to where? and who’ll pick up the kids from school? – as does, I think, the very notion of the degree in creative writing. Writing is something done elsewhere, by other people. Which makes it natural to ask: How do I become a writer? How do I get into writing? Where can I learn how to write?

But if we have a language, and if we are among the 80% of the population with functional literacy (in the UK), then we are already writers. We write notes, messages, texts, Instagram captions, Facebook posts, WhatsApp group chats, and more. We keep journals, diaries, notebooks, and memos. We write on our hands, on our bags, on walls and bus shelters and banners and streets. We know how to write. We do.

So maybe what we mean when we ask how we should write is: how can we do writing that looks like that other piece of writing over there, by that other writer? (We also, maybe, mean: how can we get paid? Which is entirely reasonable – it takes a particular kind of background to say you can give your time to making work for free – but we’ll come back to that some other day.) Or, at the very least, we mean: How can we do writing that somebody else will want to read?

This week’s assignment:

At this point in a class, I’ll usually start talking – not for the first time – about letters. One of the several things that interests me about letter-writing is that whereas the writing many of us do on social media is ‘public’ to varying extents, and could be aimed towards any number of different readers, a letter is always written to a specific person. When we write a letter, we know who our reader is, and we tailor our writing accordingly. We think about where that reader is, what they might be doing when they read the letter, what effect our writing might have on that reader. We conceive of our writing as an act of communication with that reader. We want, most of all, for them to make sense of our words. We don’t, usually, worry about what a letter ought to look like, or whether our letter will be better than some other writer’s letter. We revel, instead, in the idea of using our words to make a connection.

Although we do worry, probably, about our handwriting.

When I meet a new group of students, I often introduce them to Michael Kimball’s wonderful writing project, ‘Michael Kimball Writes Your Lifestory On a Postcard,’ discussing amongst other things the excitement of spontaneously translating a conversation into a piece of text. I then ask them to exchange life histories, and to write each other’s on a postcard. The results, without fail, have a freshness and vitality that would have been unlikely had I asked them to take five minutes writing a new short story.

So, if you’d like a writing assignment this week, here it is. Talk to someone you don’t know very well about their life history, and then write a letter to someone you do know well about that life. Read the article linked above about Michael Kimball’s project for some thoughts on how to approach asking someone about their life, if you like. Try to write the letter soon after having the conversation. Think about the details that stand out for you. Think about the narrative of a life. Think about the person you’re writing to, and how you can make this story make sense for them. What will intrigue, engage, amuse, or otherwise keep them reading to the end? What can you include in your letter that will make them want to write back?

In this exercise, we’re not worrying about what writing is supposed to look like, or about what other people are going to make of this. We’re not going to show the rest of the class. I’m not going to give you a grade. You’re going to have a conversation, find out something new, and offer that something to someone you love.

Enjoy it. Remember to use the postcode. Let me know how you get on. And trust me: your handwriting is not as bad as you think it is.

If someone forwarded this to you, or you’re reading it online, then you’re welcome to subscribe for more of the same, more or less once a week:

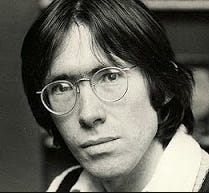

* Sidenote: I am extremely aware that in my case I do in fact look like the writers we’ve often been told writers look like. See slides A and B, below.

Next week: I’m still putting off doing any actual teaching by worrying about the notion of expertise. And the week after that, I’ll reach the peak of my powers and offer some ground-breaking and incredible thoughts about writing blurbs. Stick around.